![forest_620]()

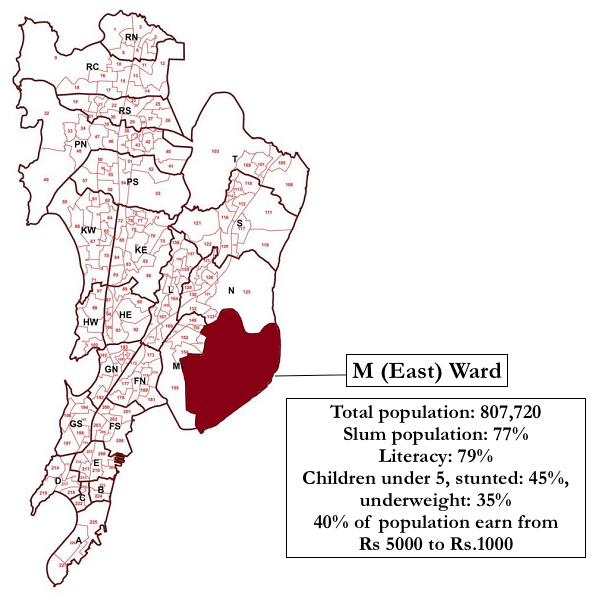

“A great silence is spreading over the natural world even as the sound of man is becoming deafening,” Prerna Singh Bindra, 45, a wildlife journalist, quotes Bernie Krause, who recorded the sounds of over 15,000 species, as she writes about the constant threat to India’s wildlife in her book The Vanishing: India’s Wildlife Crisis.

![PBS]()

Left to right: Wildlife journalist Prerna Singh Bindra; front cover of her book ‘The Vanishing: India’s Wildlife Crisis’

India, a biodiversity rich country, has just 2.4% of the world’s geographical area but accounts for 11.4% of the world’s plants (about 48,000 species), and 7.5% of its animals (about 96,000 species), according to government data.

But with habitat destruction and poaching, 25 species of animals and 77 plant species are critically endangered, 205 animals and 172 plants are endangered, while 385 animals and 138 plants are vulnerable, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

In India, we continue to clear no less than 135 hectares of forest–equivalent to 189 soccer fields–a day, diverting it for various projects such as highways, mines and cement factories, even as India’s forests neutralise 11% of India’s total greenhouse gas emissions at 1994 levels–equivalent to offsetting 100% emissions from energy use in residences and transport, Bindra writes in her book.

But India still has incredible biodiversity–the maximum numbers of tigers and asiatic elephant in the world, 90% of the gharial population, the only place with the Great Indian Bustard and Lion-Tailed Macaque, Bindra told IndiaSpend over phone, from the the Tilari forests in the western ghats, as a herd of elephants came in. “The book is about hope not despair. This is a rallying call–we can save this beautiful world if we start now.”

![reading_forest]()

“I live in Gurgaon but my heart resides in the forest” – Prerna Singh Bindra

Bindra has widely travelled across India to explore its wilderness, served as a member of India’s National Board for Wildlife and its core Standing Committee, and on Uttarakhand’s State Board for Wildlife. She started off studying management but soon realised that her passion lay elsewhere. Over the last 15 years, she has written several articles on the environment, is the author of the book The King and I: Travels in Tigerland, and of a children’s book When I grow up I want to be a tiger. She loves books, dogs and cooking but isn’t a great cook, she said. I live in Gurgaon but my heart resides in the forest, she said.

With personal stories of missing school work for the hatching of a peahen’s eggs, to moments with tigers, gharials, and the Indian bustard, to trying moments as part of India’s National Board for Wildlife, in her latest book Bindra writes about both India’s successes in and apathy to wildlife conservation.

IndiaSpend spoke to Bindra about the state of India’s wildlife, challenges in wildlife conservation, and the way forward for ecological sustainability. Edited excerpts.

Q: The book paints a bleak picture of the state of conservation in India. According to you, what are the major causes of this endangerment?

Firstly, yes, the subject is bleak. I would like to make it clear, though, that the book is not about despair, it is about hope. Ignoring the crisis is not the answer–burying our head in the sand only means we dig ourselves in deeper. The idea is to empower, to hopefully shake people up, to get a dialogue going. India has this incredible wealth of wildlife, but its current status is precarious, and this is why it matters to us.

One key cause of endangerment is poaching, which is ruthlessly exterminating wildlife. It is not just tigers or leopards. The market is driving many species to the brink—from turtles (for meat) to beetles (for private collections) to owls (used in black magic). The pangolin, an elusive, nocturnal animal also called the ‘scaly anteater’, is being trapped, snared, killed by the thousands to meet a demand for its meat and scales for international markets in Far East and Southeast Asia. The pangolin is the hottest ‘item’ in the market today, and driving it to extinction.

The problem is we haven’t taken the gravity of this crime on board–illegal wildlife trade is a multi-billion dollar industry, and is linked to terrorism and arms smuggling. We are woefully unequipped to deal with an organised crime of this scale–on average, there is a 30% shortage of frontline forest; in some reserves like Palamu in Jharkhand, it is well over 90%! The agency to deal with it–the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau–is understaffed, and not very empowered, and conviction rates of poachers are less than 1%.

The other nemesis is habitat destruction and fragmentation. India has about 20% of land under forest cover, and this is pretty much the only land now available–for industry, real estate, infrastructure, and agriculture Just about 5% of India is under the Protected Area network, and these are increasingly islanded in a sea of people. Reckless development is fragmenting even this minuscule part of India, with railway lines, highways, canals, wires criss-crossing the reserves; plus there are villages, temples, townships, reservoirs, mines within these areas, and in their immediate vicinity.

There are other anthropogenic pressures. For example, Sariska in Rajasthan has about 200,000 heads of cattle within and around the reserve, which competes with other ungulates (hoofed mammals) and also increases human-wildlife conflict.

Forest corridors connecting these small, islanded tracts of forest are also being destroyed. For wide ranging megafauna like tigers and elephants, this signals trapped populations and a genetic dead-end leading eventually to human wildlife conflict, inbreeding and inevitable local extinction.

![elephant]()

The Asiatic Elephant walks through the Mudumalai Tiger Reserve in Tamil Nadu.

But the single biggest threat, the root of this crisis, is the collapse of political will and support to conserve wildlife.

Q: “The extinction of wildlife would likely be caused not just by the greed of poachers, but equally by the rapacity of developers,” you write in the book. Why do you think that the current model of development is flawed from the ecological perspective?

The problem with the current model of development is that we measure it within the narrow confines of GDP (gross domestic product), which is riddled with problems. For example, glaring income inequalities are not reflected by it. Felling forests to mine the iron ore beneath means increased GDP (income from timber and minerals), while a standing, biodiverse forest which absorbs GHG’s (greenhouse gases), rejuvenates rivers, nourishes soils, influences monsoons has no value. We need a measure, even if it is used parallely, that along with economic growth, assigns value to natural resources, environment, well-being, and factors income discrepancies etc.

The other concern is the prevalent view that, for the sake of its development, India should ignore environmental costs. But this “growth at all costs’ model is not just unsustainable, it’s suicidal. Natural resources are finite, and they are running out–as per a 2008 report by Global Footprint Network, we need ‘two Indias’ to provide for its consumption and absorb its wastes.

It is flawed as it does not factor in the humungous costs of ecological damage. For example, mangroves are being destroyed at a massive scale–we have lost about 35% forest cover the past century for ports, tourism infra, real estate etc, even as we know that mangroves provide a shield against flooding from devastating tsunamis and storms. This was established also in the 2004 tsunami where villages with good mangrove cover faced minimal damage. The proposed draft Wetland Rules of 2016 will further dilute the protection afforded to this crucial ecosystem. Wetlands host a variety of waterfowl and rare mammals like fishing cats, recharge groundwater, help mitigate floods and support livelihoods.

There is a proposal to mine in one of the finest Sal forests in central India, rich with wildlife—including the occasional elephants and tiger, the catchment of two perennial rivers, and supports livelihood of over 50 villages—for coal which would be exhausted in 14 years.

Going ahead with the expansion of the Kanha-Pench highway will split one of the world’s most important tiger habitats, even as there is an alternative, if a longer route.

What I find an alarming, almost dangerous trend is the myth that has been perpetuated–that environmental laws and regulations are impediments to economic growth. So to facilitate ‘the ease of doing business’ we are dismantling the environment laws, regulations and policy that are the backbone of environmental governance in the country.

Q: You have been blistering in your indictment of the government and the National Board for Wildlife. What are major gaps that you identify and why do you think all Indian governments in the past two decades have ignored wildlife conservation?

The mandate of the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) is conservation; yet, in the two years starting May 2014, it rejected less than 1% of projects inside and in the immediate vicinity of Protected Areas! Many of these are damaging to wildlife–a few among them include the Ken-Betwa river linking that would drown, disembowel and split Panna Tiger Reserve; a road through Kutch Wildlife Sanctuary that would endangered the flamingo’s only nesting site in India; the missile-firing testing system on the ecologically fragile Tillanchong island, which is home to the endemic the Nicobar megapode.

I was part of the Board between 2010-13, and we consistently sought to address the fact that the Board was being reduced to a rubber stamp to facilitate clearance of projects which would be detrimental to wildlife (incidentally during 2009-14, only 12% projects were rejected), while its mandate of conservation was taking a backseat.

It is not only about the number of rejections, but about governance of such decision-making bodies, which are purportedly independent but have been rendered toothless. Agendas (for meetings) are circulated at the 11th hour, with insufficient information—so how is it informed decision-making? It is an issue of transparency and governance? Agenda of the meetings are rarely in the public domain.

Successive governments have relaxed environment safeguards painstakingly built in the 1970s & ‘80s in order to promote industry, investment, and infrastructure. The Environment Impact Assessment on the basis of which the ecological and social desirability and feasibility of a project is decided was diluted in 2006 to make it easier for industries and other projects to get approvals. The EIA is also is carried out by private consultants engaged by the company/project proponents, and rarely does it give a true picture of the environment impact. The Coastal Regulation Zone has been tweaked no less than 24 times since its original notification in 1991, each to allow and accommodate construction in eco-fragile areas just 500 metres from the sea.

So yes, I have been critical as governments have abdicated their responsibility to conserve wildlife and provide for a healthy government. In its own report of 2015 (‘Environmental Governance: Two years of NDA’) , the government lists as its achievements–in a chapter on ‘Protection of Wildlife’–the projects cleared by the NBWL’s standing committee such as construction and expansion of roads through protected areas, and the expansion of gas fields in elephant habitat etc

Q: You mention Project Tiger, India’s conservation effort for its national animal which started in 1973, as an example of a successful conservation effort. Could you explain why you consider this a success?

I call Project Tiger a measured success. Tiger numbers are no way to judge the success or failure of Project Tiger. They are a barometer, and they indicate that, since its inception 45 years ago, tiger numbers have remained stable–a remarkable achievement, given that human population has spiked since then; and the pressures of competing land uses–development, infra and industry projects–have increased manifold.

Another success is the protection was accorded to preserved varied ecosystems (as was the original mandate)—the mangroves of Sundarbans, the sal forests of Corbett, dry teak forests in Melghat and so forth. From nine reserves in 1973, we have 50 now. Admittedly, a few are poor examples with abysmal tiger densities, it does mean that we have a greater forest area that is legally protected and given enough protection, can have a thriving tiger population.

![Tiger]()

Tiger spotted sitting in Ranthambore National Park, Sawai Madhopur, Rajasthan.

In reserves like Palamu (Jharkhand), it was documented that streams that had reduced to seasonal were now flowing perennially after a year or two after it was made a tiger reserve in 1973. And under the Project Tiger umbrella, other species flourished—the hardground barasingha down to critical numbers was revived thanks to the protection afforded in Kanha tiger Reserve, while in Dudhwa Tiger Reserve, the Bengal Florican and fishing cat continue to thrive.

Project Tiger’s greatest failure is the rapid decline in tiger occupancy across tiger landscapes and the eradication of the landscapes themselves. It has failed to arrest the local extinction or near-extinction of tigers in many habitats.

Again, merely creating reserves is not enough–many of the reserves are far from optimum tiger density, poorly managed, not secure. It has failed to address or provide succour to tigers outside the Protected Area network.

As I point out in The Vanishing, there is simply no room for complacency. What made Project Tiger a success was primarily a strong political will and a zeal for the mission… it’s collapsing.

Q: What could the world learn from India in its conservation efforts?

The big takeaway: The art of the possible. If you look at it, in some ways it’s almost as if the economical and political conditions of the country are contrary to conservation: India is soon to be the most populous country in the world–with about 17% population and just over 2% of the world’s land mass. We have grinding poverty alongside being an economic powerhouse, with high aspirations of a double-digit growth, with its resultant pressures.

Yet, wild predators such as tigers and leopards, and megafauna such as elephants and bears, continue to thrive among a human population of 1.3 billion–and counting. While predators have mostly been wiped off in most of Europe and America, India’s people are remarkably accepting of predators in their midst: it’s intrinsic in our culture, a respect for life, call it what you will, it is remarkable, and something to be proud of.

Both Project Tiger and Project Crocodile were pioneering initiatives of their time that revived critically endangered species.

The lesson here is we can conserve, if there is the will from both–governments which provides the legal institutional framework, as well as the people, whose cooperation is integral to any conservation project.

Q: India is moving to solar, wind and other forms of renewable energy, which are largely considered “green”. But, in your book, you raise questions about the use of this technology. What are the main issues and how could India ensure ecological sustainability while providing safe and reliable energy to its citizens?

There is no doubting that renewable energy must be a critical part of our energy basket–but there is a need to reassess the way we are doing it. Renewable energy projects such as wind and even small-hydropower projects propagated as environmentally friendly are mostly exempt from Environmental Impact Assessments and public hearing–hence circumventing both environment and social scrutiny.

If we consider wind and solar energy, they are both very land intensive and have caused extensive damage in some of our most biodiverse areas–from the fringes of Bhadra Tiger Reserve in the Western Ghats to the Thar desert, and in the habitat of the last remaining Great Indian Bustards (GIB). Reports from Thar suggest that GIBs have abandoned the sites. Small hydel projects cause massive deforestation, pillaging ecologically vulnerable valleys–particularly in the Himalayas, the Western and the Eastern Ghats.

![great indian bustard]()

A Great Indian Bustard walking in Naliya grasslands, Kutch, India

There is no easy way forward. But I would suggest three things with the underlying principle that the choices we make have to strive for both India’s energy as well as ecological security.

First, remote decentralised renewable energy. We need solar panels on rooftops, instead of the heavily polluting diesel generators that most gated colonies and corporate houses rely on. A chunk of urban and rural needs can be met by such localised units.

Second, renewable energy projects must go through environment and social assessments, and some critical areas need to be marked as no-go. Forest diversion should take into consideration the forest diverted due to roads, linear intrusion etc.

Third, we also need to think parallely of other forms of energy for our varied needs—for instance, the use of improved cook-stoves in rural areas, greater use of bio-gas generated from cattle dung and human waste.

Fourth, demand side management is critical and here energy efficiency needs to take priority. India loses about 23% in transmission and distribution, and while the country invests heavily in new power projects, there is a huge investment shortfall in plugging these losses.

The use of energy-efficient appliances also helps lighten the power footprint.

Last but not least, we also need to ask that inconvenient question: Is the current consumption of energy sustainable?

Q: How could the issue of conservation become a priority for the government?

The ecological crisis is glaringly missing in public discourse. In 2017, five states went to polls, three of among these–Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand–have nine of the most polluted cities in the world; yet, tackling pollution had no place in the electoral debates, dialogues and campaigns. Not surprising then, governments are dismissive of the problem. We need to make it a decisive factor in elections.

People have to drive the environment agenda–it’s happening in China, where people have taken to streets–by some estimates, there are over 150,000 protests on environment issues annually. The government has had to respond to this new political reality, and take action. I am citing the China example, as it is a country our leaders love to emulate, and because they are facing the environment brunt of the “grow now, pay later” model.

We have to change perceptions, draw the links between forests and water, environment and health. Pollution is a public health issue–it is taking 1.2 million people annually to an early grave. Environmental issues are livelihood issues. A sea roiling with plastic and grime, and an overdeveloped coast is bad news for both–turtles (or whales or dolphins); fisherfolk whose livelihood collapses, and us, who are forced to eat fish stuffed with plastic and pollutants. Gharials (an endangered crocodilian species) need free-flowing, clear rivers alive with fish, which is precisely what we need for our survival too.

In a democracy, it is the electorate that guides the policy of the government. If people take up the cause, make it a movement, then we have hope that environmental issues will become electoral issues—and a priority for governments.

Governments must also internalise that the cost of environment degradation is negating the gains of growth. The World Bank stated in 2013 that environmental damage costs India 5.7% of GDP each year.

Q: Going forward, what could India do make development more sustainable not only for more Indians, but also for its wildlife?

Some areas are simply no-go–Protected Areas, other key wildlife habitats and corridors, contiguous forests, water catchment areas. India needs to up its ante on Protected Areas, increase its protective cover. Currently, these areas cover a mere 5%–less than most of our neighbouring countries. For example, Nepal has over 15% of its land under Protected Areas. Globally, 15.4% of the world’s terrestrial areas, and 3.4% of the seas are protected.

Of course, it must be effective protection.

Development must factor in environment and wildlife considerations, as well as social costs.

Conservation needs to be mainstreamed–in education, media, planning, development. It needs to be part of all disciplines–be it health, engineering, mining, construction, hydrology, the works. Wildlife and environment concerns have to be intrinsic to every aspect of planning–if we are planning highways, we must have a roadmap from the ecological point of view: Which are the areas with high ecological value that must remain roadless, which areas is it that where benefit to people in terms of connectivity, employment outweighs the environment harm.

We seriously have to consider alternatives to ecologically destructive projects: Why was the expansion of NH 7 bulldozed through even as there was an alternate route even if it meant an extra 60-90 minutes?

Proper environment, ecological, social impacts of projects are a must, as is a cost-benefit analysis. For example, the river-linking project has been heavily critiqued for its humongous costs–economical, social (massive displacement), and ecological (submergence of forests, reserve). Will it really end our water woes? Have we thought of alternatively increasing efficiency of current under-performing infrastructure, rational cropping patters, harvesting rainwater, efficient demand management etc?

It will mean tough choices: For example, should one build a port that threatens the Pulicat Bird Sanctuary, which hosts thousands of migratory waterfowl each year and supports over 40 villages?

Development has to be inclusive, truly sustainable, and not undermine the future. It has to balance the immediate and the enduring.

(Shah is a reporter/writer with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”

![]()

(@danielocarmon)

(@danielocarmon)